As a former agency owner, I know first-hand the importance of measuring marketing performance accurately. In the world of Direct-to-Consumer (DTC) marketing, the gurus you follow on Twitter will tell you that the Marketing Efficiency Ratio (MER) is the overriding measure of success. However if you blindly follow their advice, you’re going to run into serious problems. I’ll show you what I mean, and give you my solution.

Why is MER Useful?

Simply put, MER is the ratio of total revenue to total spend on advertising. You may have heard it called ‘blended’ ROI, because you’re blending both paid and organic revenue. There’s a lot to like about it as a metric. It’s simple and straightforward, that’s easy to understand and calculate, especially for small brands and hard-to-measure channels.

MER = Total Revenue / Total Advertising Spend

Why is MER Useful?

MER solves a problem you often encounter in advertising, which is that not every dollar of revenue you drive is captured in your attribution. You see this ‘halo effect’ where whenever you spend more on ads, you get more people coming back through organic channels and brand search terms. Your ad campaigns should get credit for this, but it’s hard to properly measure.

Attribution is not a solved problem, even for massive brands with 10x your resources. It just got a lot harder with all the privacy settings and legislation implemented. So in the early days of a new brand this is a perfectly valid way to make sure you’re not underinvesting in hard-to-measure channels like YouTube, Influencers, or Podcasts. It provides a canonical answer to how well you’re doing overall, keeping you honest by acting as a sense-check when in-platform metrics from Meta and Google are being greedy and overclaiming credit.

They call it something different, but many big brands use MER to set their advertising budgets too. When you’re investing in long term branding campaigns it can be impossible to trace back exactly what dollar spent on TV ads led to that purchase 5 or 10 years in the future. So they benchmark the Advertising-to-Sales Ratio for their industry, and decide if they want to over or under invest relative to competitors. It’s only in the messy middle when brands are scaling that they care about attribution, and need to make every dollar count.

When is MER a Bad Metric?

The problem with MER is that blindly following it can completely derail your entire business if you do happen to be in that phase where every dollar counts. As brands scale and advertising becomes a smaller share of total revenue, MER becomes a less reliable metric for sense-checking the performance of your ads.

The problem with MER is that as your brand scales, you start to see growth coming from other areas other than advertising. As you do well in other areas, your revenue increases, which then prompts you to increase ad budgets, even though they weren’t responsible! For example:

- You start to get more word of mouth, because your user base is bigger.

- You do a distribution deal with a major retailer which drives online traffic too.

- You get featured by the press which builds awareness of your brand.

- You begin ranking higher on Google for key commercial terms.

- You begin experimenting with harder to measure channels and branding.

This is bad enough, but given enough time you’ll also run into macro factors that are completely out of your control, which also affect sales. These factors aren’t correlated with your ad spend, but they do seriously affect your results. Again if these trends spike or dip your revenue, you end up adjusting budgets for no good reason. For example:

- There’s a global pandemic and local lockdowns lead to a surge in online sales.

- The economy is in recession and unemployment is high, so sales plummet.

- It’s Black Friday and tons of shoppers are out browsing for bargains.

- Your competitor is running a big TV campaign, growing awareness of the category.

- Your brand goes viral on social media because a celebrity posted about you.

Any one of these factors might affect your revenue, and yet they’re completely unrelated to the ad budget you set this week or month. Now what happens if you’re setting your ads budget based on the total revenue figure? Well you’re either pouring gasoline on the fire, or pumping the brakes, due to factors entirely unrelated to ad performance!

You could be lighting that money on fire, or pulling back exactly at the wrong time. That leaves less money left over to invest in other channels that may be more incremental, or to scale up the business in other ways through stocking inventory or doing distribution deals.

MER Example

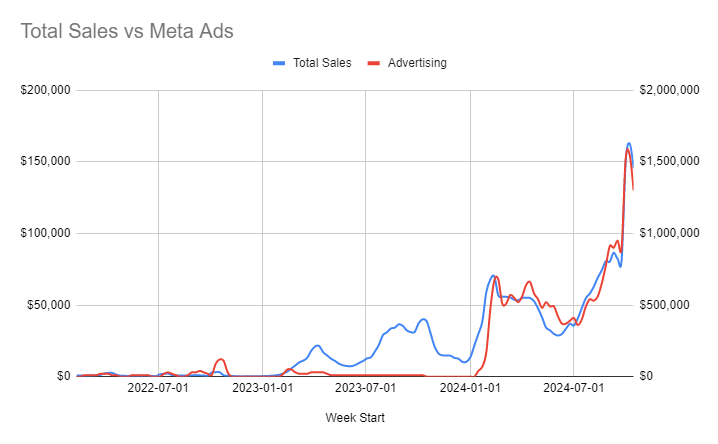

Let me show you an illustrative example that I’ve seen in the data multiple times. In this example the client starts spending on Meta Ads, and honestly they’re pretty happy. Sales are up, and so their agency deploys more spend automatically. Then the founders get invited to feature in an episode of Shark Tank, and sales spike. Their agency is quick to react: don’t want to miss this opportunity! They dutifully put the foot on the accelerator and spend 2-3x the normal budget (the spike on the far right of the chart).

What’s wrong with this picture? Well for one Meta Ad spend seems to be lagging Revenue: that means Sales go up, and spend follows after. The exact opposite of what you want! What you want to see is that when Meta spend goes up, Sales goes up that week and in the weeks following. That would indicate that the Ad spend is causing Sales to increase, i.e. that ad spend is driving sales. Your ad spend and revenue are correlated, but only because you forced them to be correlated by setting an MER target.

Now of course this spend might be incremental, and it will certainly have had some positive impact, but how much? If you hadn’t increased your budget, might you have made more profit that day because the increase in costs saturated the channel and killed your returns? You don’t know, because you didn’t do any proper measurement of that spend. With this method, there’s no discernible difference between a team that spent $150k reaching your target customers with well-optimized creative, and one that just dug a pit and buried it in the ground.

Giving your agency free license to spend alongside Sales is a miscalculation: the more success you drive from other marketing initiatives, the more Advertising costs go up. Most people who work at agencies are honest, but they typically get compensated as a percentage of ad spend: they won’t say no if you ask them to spend more money. Ultimately it’s you that has the responsibility to measure the effectiveness of your advertising. You need to align the incentives of your team and vendors so that they make money when you do, not when you increase costs.

Triangulating the Truth

The goal of marketing measurement is to estimate what marketing channels are driving incremental sales, i.e. sales that wouldn’t have happened without the money you invested in the channel. If sales are actually being driven by your appearance on Shark Tank, or any number of other factors, the extra money you spent on advertising might have been a waste. This is the trap you can fall into when using MER.

However you started using MER in the first place because marketing attribution isn’t a solved problem. You can’t afford to overinvest in advertising when Shark Tank drove sales, but equally you don’t want to underinvest in advertising by not measuring their halo effect on organic. There’s no easy answer, and brands spend millions of dollars with advanced teams of data scientists to try and estimate marketing contribution.

There is one solution that is emerging from the post-iOS14 fallout, that everyone seems to be converging on. I’ve found it personally useful in the past, and it keeps coming up in conversations with Meta and Google, as well as friends and clients in the industry. It’s called “Triangulation”, and this is how it works:

- MTA (Multi-Touch Attribution) i.e. platform-reported metrics for daily or weekly optimizations at the ad set or creative level.

- MMM (Marketing Mix Modeling) for allocating budget across channels or campaigns, and adjusting the incrementality of platform-reported metrics.

- CLS (Conversion Lift Studies) for calibrating your MMM, and making sure its recommendations are accurate compared to experiment results.

You can get extremely complex with it, but the way it works in practice is to use the strengths of each of these methods to zero in on the actual truth. CLS can be expensive to set up and run, and it’s not possible to test everything all the time. So you use the results of the tests you did manage to run, to make sure the MMM that you build is honest, which then helps you adjust what you see in platform reporting.

For example, if your model says TikTok drove $100k in revenue last month, but the lift test you ran indicates it was actually $150k (because of iOS14, those people were bucketed as ‘organic’), you need to rework the model until it gets in sync with the findings of your test. Once the model agrees with what you know from testing, you can have faith in the model.

MMM then fills the gaps for the channels you haven’t tested, and can be used to adjust what you’re seeing in the platform. For example if you just started running Meta Retargeting, but haven’t done a lift test yet, what the MMM says about it is your next best opinion. If the model says retargeting is only 40% incremental, multiply what you see in the Meta Ads Manager by 0.4 to get closer to the true figure.

I have also found it helpful to add another attribution method into the mix, which is Surveys, particularly a “How Did You Hear About Us” survey right after the checkout or registration page. This can act as a further sense check against your MMM, and can inform your experimentation roadmap by identifying potentially underperforming or overlooked channels. I didn’t include it because then there would be four sides, and it wouldn’t be a triangle.

Is Triangulation For Everyone?

Is this easy to implement? No. Is it necessary for every brand? Also no. CLS and MMM are both difficult practices which require significant investment in time, money, and expertise. In my experience, unless you’re running at least two channels and making more than $1 million a year in revenue, you shouldn’t think about attribution at all. The same goes for if you’re spending on every major channel and doing $1 billion in revenue per year. If you’re somewhere in the messy middle, it’s time to get wise on your approach before your boss or an investor does.