Early on in my career, I learned a valuable lesson in incrementality that I’ll never forget. Ever since I had this experience, I carefully avoided making the mistake of trusting an advertising platform’s reporting without independently verifying the sales they claim wouldn’t have happened anyway. Hopefully you can learn from this example, and avoid it happening to you.

I won’t share the name of the company, people, or vendor involved, and have changed a few small details to protect privacy. Regardless of the outcome I still believe everyone involved were honest, hard working people, who just happened to get on the wrong side of proper attribution due to poorly aligned incentives.

Work Trip

I was a relatively junior marketer at the time, working in London, and so I was extremely excited to get an opportunity to go over to the States. My boss at the time wrangled us an invite from their boss, who was based in the company’s San Francisco office. I was drinking the silicon valley kool-aid at the time, with dreams of one day starting my own innovative tech startup.

The trip was fun and informative, and I met some interesting people. Our Google rep came through for us, so we got to visit the famous campus, and got our chance to overindulge at the lunch buffet. While there we also got taken out for a fancy meal by our display advertising vendor, who casually mentioned we should start spending on their platform in Europe too.

I was surprised display took up so much of the U.S. team’s budget, given it was mostly Google Search ads that worked for us: we had tried, but couldn’t get display ads to perform. They explained how their platform used machine learning (innovative at the time) and they seemed confident they could deliver. I was young and impressionable, and I promised to try their platform out when we got back home.

Display Ads Test

We ran a small scale display ads campaign with their team, who were super knowledgeable and smart. I was impressed by their targeting capabilities, and the way they used machine learning to not just optimize, but indicate what features in the model drove value. The results were indeed good, perhaps too good to be true…

Looking into one of the reports, I noticed that 90%+ of the conversions recorded were “view-through”, i.e. they didn’t click the ad, but it was shown to them and they later converted. I also noticed that the majority of the performance came from retargeting existing site visitors, rather than prospecting for people who hadn’t already visited our site.

I suggested we run an incrementality test to sense-check the results, before we could commit more budget. I came from an economics background, and had graduated recently enough to still remember the difference between correlation and causation. They told me they didn’t offer that functionality, which wasn’t unusual at the time. That’s when the trouble started.

Conversion Lift Study

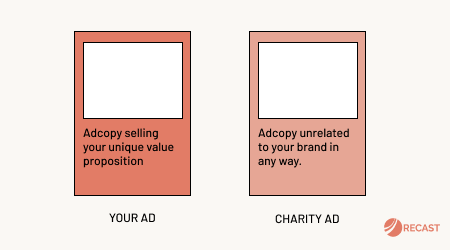

I was precocious and eager to impress, so I decided to hack my own little Conversion Lift Study (CLS), in order to look smart. I used the “charity ad” approach: put your ads in even-rotation but replace one of them with an ad for an unrelated charity of your choice. If that charity ad records any conversions, you can be fairly certain that is the baseline for how many customers would have converted anyway.

I honestly expected to prove beyond a doubt that this cool new platform really drove results, that machine learning was the future, and get showered in more budget to spend. You’re already aware this is a cautionary tale, so you know what happens next. The lift study said that 60% of the reported conversions would have happened anyway! Display advertising through this advertiser was only 40% incremental.

This was a surprise, but I still didn’t see the problem. Know we have proven 40% incrementality, we can simply adjust the spend downwards until the cost per incremental conversion, cost / (conversions * 0.4), was within range of our efficiency target. This works because of diminishing returns: if a channel is inefficient at your current scale, you can cut back and “harvest the low-hanging fruit”, getting a more comfortable return on investment at a lower monthly spend. We published the results in our weekly report, and sent our recommendation up the chain of command as we’d usually do when we found an interesting result from our analysis.

Political Repercussions

Maybe I was being naive not to expect this, but the resulting fallout was a surprise to me. Later in my career looking back, I realize I got lucky: in more political organizations I would have had blowback from calling out a senior leader, and harming the relationship with a key vendor. My boss did get a snotty email, but they shielded me from any political repercussions. Ultimately the findings made their way to the CEO, who then demanded they run the same test on the multi-million dollar U.S. budget. They found the same thing we did: display was only ~40% incremental. The CEO actually ended up firing my boss’s boss for wasting so much money, and not showing the initiative to proactively run a test like this sooner.

Interestingly enough, we didn’t end up firing the vendor. The CEO did slash the budget in half, and re-organized the team now they were without a leader, but ultimately it did turn out to be a good channel for us, driving 5% of all our sales at a breakeven incremental Return on Investment (ROI). The question we should be asking with conversion lift tests is not “should we turn this off?”, but “how much is appropriate to spend?”. I took this experience with me into founding my own marketing agency, and you can bet I did everything possible to explain to my clients and team the importance of incrementality, so we’d never get caught in that position. It was a valuable lesson, one I’ll be slow to forget.